How many times each day do you use an app on your smart phone? once? twice? dozens? Most of us use apps almost without thinking—they have become a part of the way we work and play. You are no doubt very aware of how apps are changing how you travel (buy a ticket, check in, reserve a car, find the nearest coffee, get a weather report and on and on). And there’s a visible impact on our shopping, with apps for all the major online shopping sites becoming more and more popular.

At latest count, there are at least 700,000 apps EACH for iPhones and Android smart phones. That’s a lot of apps. Just as you might expect, some are good and some aren’t. Remember about 10-15 years ago when everyone rushed to build a website? Some worked, some didn’t. We’re going through the same thing with apps right now.

Apps that don’t deliver what the consumers want are quickly abandoned. One thing to keep in mind is that people don’t necessarily use smart phones in the same ways they use a full size keyboard and monitor or even as they use a tablet. Building an app that mimics too closely how people interact with a traditional website may be a mistake. Each display option has its own advantages, and app developers need to recognize and take advantage of particular platform features.

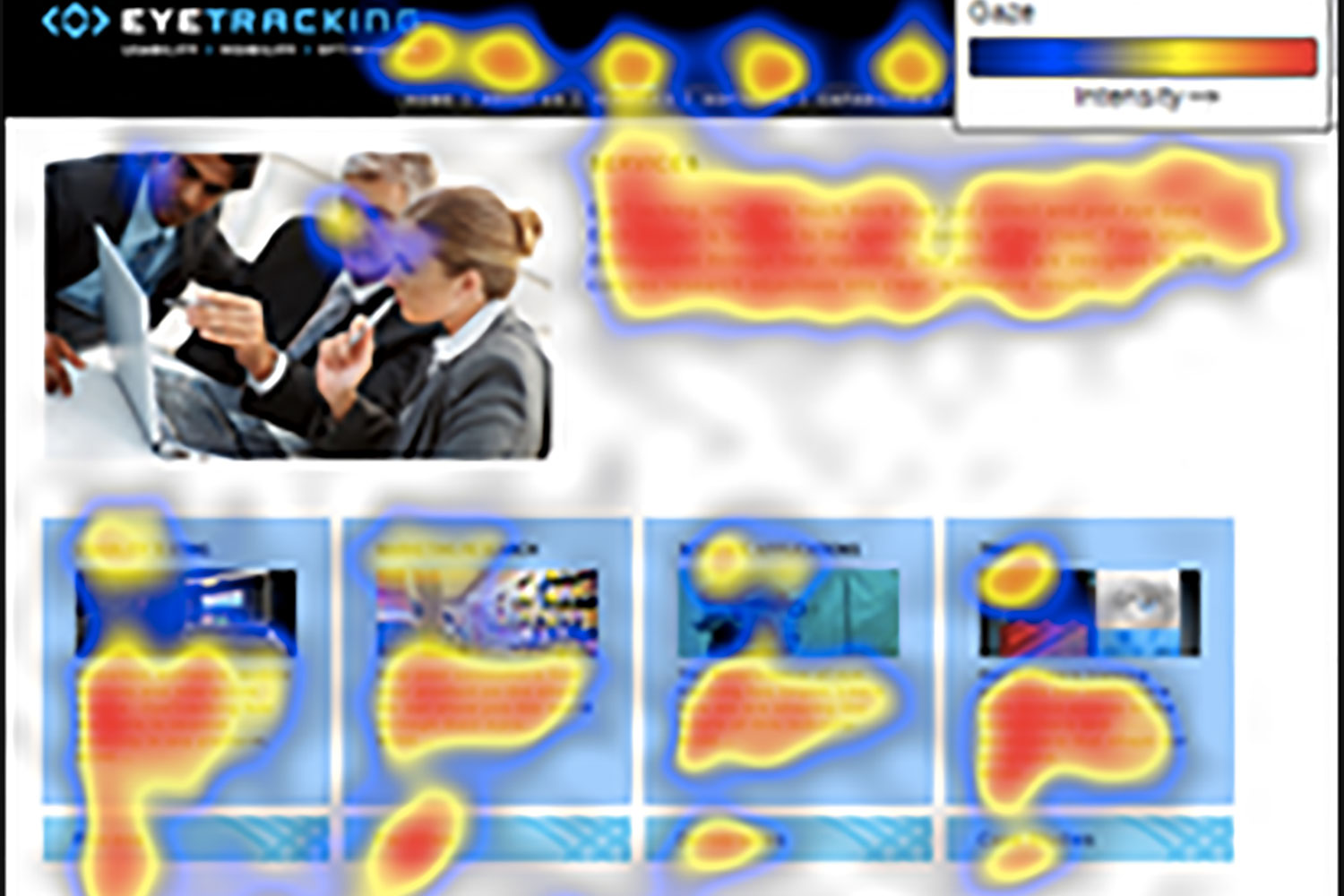

What does eye tracking have to do with all this? Just as savvy commercial entities routinely carry out usability studies on their ecommerce websites, they are now beginning to do similar studies on their smart phone apps. The only way you are going to find out if your customers see the major features on your app is to follow their eyes as they use it. Users’ interactions with a smart phone app are far quicker than their interactions with a traditional computer website. It takes only a fraction of a second for your users to scan the phone display and move on. Do you know what they saw? Are your navigation features clear and visible even when the user is swiping or scrolling? The real estate on a smart phone is valuable—you can’t afford to waste any of it. And, time is precious—milliseconds matter, because transactions take at most a few seconds. Usability testing can improve the way your app functions and make it more valuable for you and your customers.

Featured image from Unsplash.